Biography

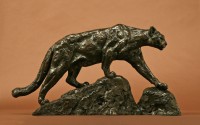

By Todd Wilkinson The Master: Ken Bunn, American Animalier There are myriad ways to assess artistic standing in the world. Almost invariably, however, final verdicts are seldom rendered by artists. When the late Jeanne Hopkins passed away, she wanted to solidify the legacy of one of her favorite animal sculptors. The devoted patron of the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson, Wyoming, generously set aside money in her will to commission a piece by American Ken Bunn (b. 1935). In the summer of 2014, the fruit of her gift—Bunn’s larger than life-sized ode to a lone gray wolf [yet untitled]—will be unveiled at the museum’s outdoor sculpture promenade overlooking the National Elk Refuge. The first major wolf in the museum collection, it is Bunn’s third major piece to be installed at the venue, among an array of smaller works in the permanent vault, but many believe this could be his most iconic; even more resonant than his signature prowling mountain lion monument adorning the museum’s great interior hall. Some say that considering its commanding setting, Bunn’s lobo is akin to the Capitoline she-wolf suckled by Romulus and Remus that resides at Musei Capitolini high above the ruins of ancient Rome. Adam Duncan Harris, the wildlife art museum’s chief curator, says Bunn’s selection to portray an archetypal canine predator not only honors him, but it validates his position as a creative force in wildlife sculpture for 50 years. “In any scholarly art discussion, Ken Bunn’s name is always prominently mentioned in the conversation about who justly should be regarded as the great wildlife artists of the late 20th and early 21st centuries,” Harris says. Bunn, known for being a sociable wild man in his youth, is an artist who eschews publicity. Sharp, agile and creatively vigorous as a late septuagenarian, he has, for years, quietly gone about delivering a number of impressive large pieces to public venues and private collections often flying under the radar screen of notice. Sculptor Tim Shinabarger, who has received acclaim as a stylistic successor of Bunn, credits him with having an influence on generations, particularly those who favor a more impressionistic, rather than literal, portrayal of animal forms. “Ken is able to use this lumpy, bumpy technique and out of cold bronze he gets vibrations that play across his variegated surfaces. There’s a lot going on but once you stop back you see the brilliance with how the vision crystallizes. How he brings out the personality of an animal is amazing,” Shinabarger says. “As an elder, he is, for me, the living king when it comes to wildlife sculpture.” Any royalty reference aside, humility is a working principle drilled into Bunn long ago by his first mentor, Coloman Jonas (1879-1969), who presided over the globally-renowned Jonas Brothers taxidermy company in Denver where Bunn, a native of the West, got his start. “That was my art school,” he says. Jonas Brothers prepared specimens of mammals and birds from around the globe that still adorn the most notable natural history museums. They are distinguished by the artful flair brought to animal poses. Under Jonas’ tutelage, Bunn sculpted precise molds for animal mounts based upon an understanding of the species’ underlying physiology and musculature. He made animal death masks and reconstructed subjects from the bone level up. That knowledge, critics say, is fundamental to Bunn’s mastery of mass and flow in his subjects. It also lays the foundation for his graceful and stylish approaches to texture and carefully-crafted surface planes that appear to shape-shift under changing light conditions. Bunn’s apprenticeship coincided with the arrival at Jonas Brothers of African sculptor Robert Glen who is not only Bunn’s across-the-Atlantic friend but, like him, a person drawn to the style of 19th century European animaliers. After auditing a medical student anatomy class as a teenager at the University of Utah in the 1950s that featured human cadavers, Bunn prodigiously earned an internship with the giants of taxidermy at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. It led him back home to the Mile High City and Jonas Brothers. Colomon Jonas wasn’t a touchy-feely coddler. “Nothing was ever judged to be so good that it couldn’t be improved upon,” Bunn says. “Coloman wasn’t the complimentary type. His favorite tool for offering critiques was a hammer that he would use to smash and obliterate whatever you were working on. It was his way of getting you back on track. When you succeeded, he said very little and you would take that as his high praise.” A routine driven into Bunn as a late teenager and which he still practices to this day is spending time at zoos filling sketchbooks with quick thumbnails and drawings. His studio, inhabiting a dusty old warehouse in downtown Denver, confirms his high standard for perfection, for in many nooks and crannies lie the scattered remains of armatures, models and castings that were either abandoned or not released because Bunn believed they had artistic flaws. “You go in there,” says Bill Rey, owner of Claggett/Rey Gallery, “and you feel like you’ve just passed through a time tunnel to a turn of the 20th century atelier, in Paris.” Bunn is counted among an influential fold of American, European and African-born painters and sculptors whose portrayals of megafauna and birds helped popularize wildlife art in the modern age. Their adventures pursuing and being chased by African beasts, ranging from lions and rhinos to elephants and Cape Buffalo, are legendary. The group includes Glen, Robert Bateman, David Shepherd, Ray Harris Ching, Kent Ullberg, T.D. Kelsey Jonathan Kenworthy, the late Simon Combes and Bob Kuhn—the latter considered one of the best mammal painters of all time. An academician with National Academy of Design and fellow of the National Sculpture Society, Bunn has work in the permanent collections of the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, the Autry National Center of the American West in Los Angeles, the Eiteljorg in Indianapolis, the Royal Ontario Museum, Denver Art Museum, Columbus Museum of Art, and the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, where he received the Robert Lougheed and Frederic Remington awards. Nowhere is he held in higher esteem than at the National Museum of Wildlife Art, which honored him with the coveted Rungius Medal given to only a few artists and conservation giants such as the late Roger Tory Peterson, Wallace Stegner, E.O. Wilson and Jane Goodall. “Ken is in a Bob Kuhn-like category when it comes to respect,” says Brad Richardson, owner of Legacy Galleries in Jackson Hole and Scottsdale. “He has been for so many years the standard bearer of what quality sculpture should be. He’s etched himself a place in history as a fine artist whose mastery transcends his subject.” “You recognize a work by Ken Bunn the moment you see it,” adds Maria Hajic who has represented Bunn’s work at Gerald Peters Gallery in Santa Fe for decades. “His surface texture and suggestion of movement lend an unmistakable style. His animals strike a dynamic balance between power and grace reflecting their vitality for life. In a medium as logistically complicated as bronze, Ken creates loose, flowing sculptural surfaces that convey an underlying truth about the nature of his subject. And he makes it look easy.” Canadian painter George McLean and Bunn regard each other as blood brothers. “He has made me laugh harder, longer more than anyone I know,” McLean, who has rubbed shoulders with most of the great wildlife art masters of the last half century, says. Beyond the mirth, McLean turns serious when discussing Bunn’s work. “To me, what a large part of so-called ‘wildlife art’ lacks today is real meaning. There’s no nuance or finesse. What’s more, so much is mechanical, lacking subtlety,” he says. “Bob Kuhn’s work, drawing upon his background as an illustrator, is full of theatre. The work of Bruno Liljefors [the Swedish painter] has drama. Ken Bunn’s sculpture has drama.” Bunn’s tenure at Jonas Brothers only begins to explain his authenticity that has caused other artists to want to emulate him, McLean says. “Yes, he is one of the great anatomists in the business. And, yes, he has this deep tactile knowledge of the animal and he understands its behavior,” he says. “But Ken also has a hugely intelligent, inventive mind. A tactician will get the animal right but leave out the art. When you assess Kenneth Bunn, you don’t see a body of artwork that is consistently good. His has been consistently excellent.” Bunn considers himself “an interpretive impressionist” who identifies with the liberating attitude of the European animaliers of the 19th century who sought to break away from the perceived rigidity of classicism that ruled during the Renaissance and Enlightenment. They venerated animals for their own sake instead of only under the guise of allegory. Where many of Bunn’s own contemporaries gravitated toward the French school of animal sculpting, he is drawn to the tradition of impressionism that arose in Italy and produced , Giuseppe Grandi (1843-1894) and Paolo Troubetzkoy (1866-1938). Animaliers who came along late in the movement, Bunn says, used a phrase to describe their philosophy. “The point of their method was to make work that appeared ‘seemingly casual and rapidly executed.’ They sought to convey the creative spirit,” he explains. “You work on a piece, but the cardinal sin was to never over-render or over-refine, and never allow compositions to appear labored.” Bunn’s animals can be heroic but they aren’t stoic. Whimsy communicates levity which enables the viewer to feel the weight of a mass being lifted away, evoking a broader range of emotions and different kind of impact. Angling toward a deep chasm of space in Jackson Hole, Bunn’s wolf isn’t mythological like the one in Rome. His is a tribute to untamed wildness, not fleeing or fleeting, but pausing to take a look back into our own eyes. In terms of what constitutes monumentality, Bunn says, it has more to do with the spirit of gesture laden in the work rather than sizing up a piece based upon a proscribed dimensional scale. When I ask him what is necessary to communicate the vitality and inner landscape of a subject, he replies, “Where you find the intensity of the animal in an artwork, you‘ll also find the intensity of an artist.” Good work, the best kind, he says, is full of feeling. “It is,” he notes, “about searching for, and finding the life force.”